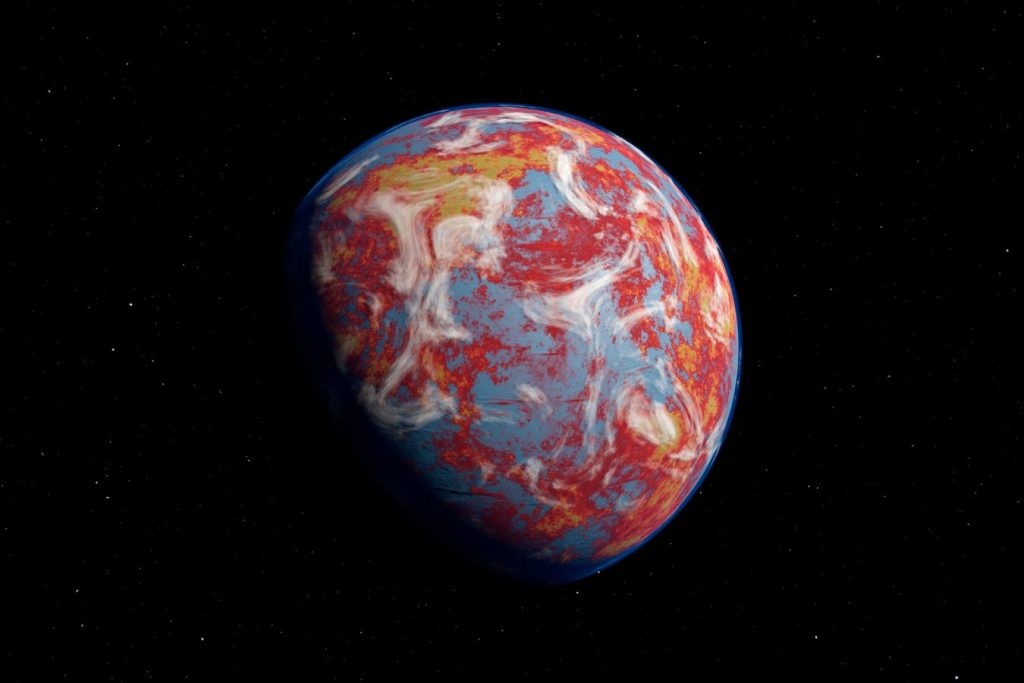

The search for oxygen may be crucial in finding extraterrestrial civilizations, but the reason is not as simple as you might think, argues a new paper. Meanwhile, a second new study suggests that planets with very little carbon dioxide in their atmosphere could be a sign of liquid water—and possibly life—on that planet’s surface.

Search For Oxygen

The fact that Earth’s atmosphere contains oxygen makes it habitable for complex aerobic life, but the element also a hallmark for the development of technological civilization on Earth—fire.

A new NASA-funded paper pubished in Nature Astronomy outlines the links between atmospheric oxygen and detecting extraterrestrial technology on distant planets, suggesting that prioritizing the search for high oxygen levels on exoplanets could be a significant clue in finding potential “technosignatures.”

Oxygen, Fire And ‘Technosignatures’

Exoplanets are planets that orbit a star other than our sun—over 5,200 of which have been found and whose atmospheres are now being studied by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope. Technosignatures are scientific evidence of past or present technology, indicating life’s presence in another star system.

It’s been argued that it may be easier to find technosignatures on distant planets that direct evidence of microbial life in the atmospheres of planets—known as biosignatures. Examples of technosignatures include radio signals, artificial light, solar panels, swarms of satellites around a planet or megastructures of some kind, and industrial pollution in the atmosphere.

Driving Force

The researchers state that fire has been the driving force behind industrial societies. Technology developed on Earth because open-air combustion—fire—is possible. Fire demands fuel and an oxidant, usually oxygen. Fire makes cooking, forging metals for structures, crafting materials for homes, and harnessing energy through burning fuels possible. They found that the controlled use of fire was only possible when oxygen levels in the atmosphere reached or exceeded 18 percent—much higher than required to sustain biologically complex life. The air in Earth’s atmosphere is made up of about 78 percent nitrogen and 21 percent oxygen, according to NASA.

“You might be able to get biology—you might even be able to get intelligent creatures—in a world that doesn’t have oxygen,” said co-author Adam Frank, the Helen F. and Fred H. Gowen Professor of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Rochester and the author of The Little Book of Aliens. “But without a ready source of fire, you’re never going to develop higher technology because [it] requires fuel and melting.”

Search For Carbon

In a separate paper published in Nature last week, scientists argue that the absence of carbon dioxide in a rocky planet’s atmosphere—relative to others in the same star system—may indicate the presence of liquid water on the planet’s surface. Earth’s lower carbon dioxide levels, compared to Venus and Mars, result from a water cycle involving oceans. Researchers argue that a similar pattern on an exoplanet could mean oceans and life. “On Earth, much of the atmospheric carbon dioxide has been sequestered in seawater and solid rock over geological timescales, which has helped to regulate climate and habitability for billions of years,” said study co-author Frieder Klein.

Distinctive Signature

Crucially, the distinctive signature of carbon dioxide is achievable with NASA’s infrared James Webb Space Telescope, argue the researchers, unlike many other biosignatures. Carbon dioxide is a strong absorber in the infrared and can be easily detected in the atmospheres of exoplanets. In July 2022, JWST detected carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of WASP-39b, a hot gas-giant orbiting a sun-like star about 700 light-years from Earth. Biosignatures—such as oxygen and carbon dioxide—can be detected within an exoplanet’s atmosphere using spectroscopy, which analyzes the light that passes through the atmosphere.

“The Holy Grail in exoplanet science is to look for habitable worlds, and the presence of life, but all the features that have been talked about so far have been beyond the reach of the newest observatories,” said Julien de Wit, assistant professor of planetary sciences at MIT, in a press release. “Now we have a way to find out if there’s liquid water on another planet. And it’s something we can get to in the next few years.”

Wishing you clear skies and wide eyes.

Read the full article here